Russia’s cyberwarfare against Ukraine and the West

A month after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine had started on 24th February 2022, some commentators were wondering why they could not see any signs of Russian cyberwarfare, which was expected to accompany the bombing of Ukrainian cities. As we know now, this first impression was completely wrong.

On 1st March, The Economist published an article under the headline: “Cyber-attacks on Ukraine are conspicuous by their absence”. [1] And an article in Nature, published on 17th March 2022, asked in the headline: “Where is Russia’s cyberwar?”, followed by this first sentence: “Many analysts expected an unprecedented level of cyberattacks when Russia invaded Ukraine — which so far haven’t materialized.” [2] It is a matter of debate what you consider “unprecedented” after the already constantly high level of cyberattacks by Russia against Ukraine since the annexation of the Crimea peninsula in 2014. However, just because the massive attack was not fully visible to some Western experts does not mean that it did not take place.

Russia’s cyberattack on Ukraine

At the end of March it emerged that intensive Russian cyber-attacks accompanied the Russian invasion. In a press conference on 29 March, the deputy director of the Estonian Information System Authority, Gert Auväärt, rang the alarm bell and announced that the cyber threat level in Estonia had risen following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and the cyberwarfare efforts accompanying it. He mentioned that banks, authorities, agencies, telecoms firms, companies and other significant targets in Ukraine had fallen victim to denial-of-service or malware attacks. At the same time, Ukraine’s critical infrastructure had not been paralyzed despite the massive attacks.

Tom Burt, who oversees Microsoft’s investigations into big complex cyberattacks, commented the Russian cyberattacks by saying: “They brought destructive efforts, they brought espionage efforts, they brought all their best actors to focus on this.” He added that the Ukrainian defenders were able to thwart some of the attacks, as they had become accustomed to fending off Russian hackers after years of online intrusions in Ukraine. He praised the Ukrainian cyber defence: “They’ve been doing a good job, both defending against the cyberattacks and recovering from them when they are successful.” [3]

The conclusion from this is that the main reason why we have not seen too many devastating effects of Russia’s cyberwarfare in Ukraine seems to be that Ukrainians were defending well.

Apart from successfully defending against Russian cyber-attacks, Ukraine received effective support from Belarusian hackers.

Counter-attacks in Belarus

The first setback Russia suffered in the cyberwar against Ukraine already happened before the invasion began. A hacktivist group of exiled Belarus tech professionals called Cyber Partisans, who had been fighting against the regime of the autocratic Belarusian president Alexander Lukashenko for years, became active at the first signs of the Russian military buildup at the border to Ukraine. The Cyber Partisans attacked the Belarusian train system, which has been important for moving Russian soldiers, tanks, heavy weapons and other military equipment to the Ukrainian border. They exploited security holes in the more than two decades old Windows XP operating system on which large parts of the IT infrastructure of the Belarusian train system have been based.

In collaboration with Belarusian railroad workers and dissident Belarusian security forces, the Cyber Partisans managed to slow down Russian troop movements and supplies. This contributed to the logistical chaos of the Russian armed forces in the first weeks of the war, which left Russian troops stranded on the front lines without food, fuel and ammunition. In this way, the cyber sabotage of Russian logistics supported Ukraine’s successful military resistance against the Russian armed forces in the Ukrainian capital Kyiv and other cities in the north of the country.

Russia’s cyberattacks on Western countries

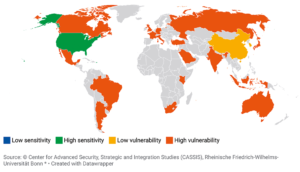

Ukraine is by no means the only target of Russian cyberattacks. Cyberwarfare by Russia against Western countries has a long history. [4] The most prominent event was the cyberattack on Estonia in April 2007. Although it had never been proven that the Russian government was behind it, the trail clearly led to Russia. Since the Russian annexation of Crimea in 2014, cyberattacks against Western countries like Germany, France, Poland, the UK, and the US have increased in both intensity and scope.

Cyberwarfare by Russia has included a plethora of different activities, from hacker attacks to disinformation. There are indications that Russia interfered through disinformation and other measures with the Brexit vote in the UK and the US presidential election in 2016.

NATO’s cyber defence

Since 2008, NATO has been building up its cyber defence, in response to growing cyberthreats by countries like Russia, China, and North Korea. A year after the cyberattack on Estonia, NATO founded the Cooperative Cyber defence Centre of Excellence in Tallinn. At the 2014 NATO Summit in Wales, after the Russian annexation of Crimea, NATO adopted an enhanced policy and action plan. It established cyber defence as part of the Alliance’s core task of collective defense and set out to further develop NATO’s cyber defence capabilities in collaboration with industry. [5]

Conclusion

At the time of writing, it is not clear, when and how the Russian war against Ukraine will end, and what types and levels of cyberwarfare will occur in within this conflict. What appears certain is that cyberwarfare has become a standard element of conflict between nations, which has expanded the arsenal of hybrid warfare. Challenges for maintaining cybersecurity will subsequently increase, making both the physical world and the virtual world a less safe place. Significant investments in cyber defence and cybersecurity will be needed on all levels, in order to ensure security and resilience of Western democratic societies.

References

[1] Cyber-attacks on Ukraine are conspicuous by their absence, The Economist, 1 March 2022 – https://www.economist.com/europe/2022/03/01/cyber-attacks-on-ukraine-are-conspicuous-by-their-absence

[2] Elizabeth Gibney, Where is Russia’s cyberwar? Researchers decipher its strategy, Nature, 17 March/ 18 March 2022 – https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-022-00753-9

[3] Preston Gralla, Russia is losing the cyberwar against Ukraine, too, Computerworld, 2 May 2022 – https://www.computerworld.com/article/3658951/russia-is-losing-the-cyberwar-against-ukraine-too.html

[4] Cyberwarfare by Russia, Wikipedia – https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cyberwarfare_by_Russia

[5] Cyber defence, article on NATO website, 23 March 2022 – https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/topics_78170.htm